After a good week-long read of ‘New in Chess – The first 25 years’, I noticed that amongst the many interviews were some intriguing analogies to other sports by leading chess players; more often they functioned as a source of inspiration, but also as a mode of reference…with varying degrees of communicative success involved.

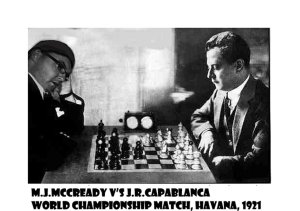

On page 62 on the ‘New In Chess -The First 25 years’, Spassky discusses his love of tennis, mentioning that the degree of similitude between chess and tennis has benefited his play in both activities. When asked to define what he meant, he said ‘Like chess [,] tennis is a game of balance, of equilibrium…Keres was a good tennis player…and so was Capablanca’. The history books tell us that if anyone ever cultivated their game so that balance and flexibility were a principle and defining aspect of it, it was surely Spassky. He qualified his remarks further by suggesting that Smyslov revealed a secret to him, that he played tournament chess like baseline tennis, ‘…he said that he used to play not with the head but with the hands. -Trusting his intuition? [Interviewer’s question]. ‘Yes because time-trouble doesn’t allow for serious analysis during the game. If you have an idea, just play it.’ We are left to ponder the significance of such remarks, which in retrospect seem more like afterthoughts than anything else. Can a world champion really find inspiration from an activity in which he is nothing more than a rank amateur…surely not?

Kramnik, also very well-rounded in his play (just check out his wins with the Sicilian Sveshnikov in the 90’s if you insist he is a dull, positional player) gives a curious, conceptual justification for the Berlin Defence in the section ‘Chess and the art of Ice Hockey’ (page 256):

‘[Interviewer] When did you decide on this generally defensive strategy? [Kramnik] I follow ice hockey a bit and the Czech national team has been winning everything in the last couple of years…they always win 2-0, 1-0, or 2-1 all the time. They don’t show any brilliance but they win all the events…the Czechs have a very solid defence. In fact there are some parallels with chess. They have a brilliant goalkeeper. In chess this is the last barrier, when you are on the edge of losing, but you sense very well exactly where this edge is. And then they go on the counter-attack. Their strategy is so clear. They have been doing this for 2 or 3 years but nobody can do anything. This idea occurred to me when they won another championship in May and I had already signed the contract to play Garry. I thought, okay it’s a different game but the approach is very interesting. And that’s how I chose this defensive approach. You need to be sure that you will be strong enough to hold. If you are not sure you can hold worse positions, this strategy makes no sense.’

What makes this point even more interesting is that Kramnik claims he hated playing the Petroff…it’s quite astonishing how someone can become respected for playing something they came to loathe so much -that is the essence of professionalism I suppose.

Lastly, on page 312, the ex-F.I.D.E world champion Rustam Kasimdzhanov refers to the following song about high-jumping:

‘-What is your favourite Vissotsky line? [Kasimdzhanov] It’s difficult to translate it into English. It was what struck me during the sixth game against Adams. He has a song called “The song of the high-jumper”. He jumps and he doesn’t quite manage. He wanted to make 2.12 and fails. And he says, I will let you in on a small secret: such is the life of a sportsman or woman. You are at the highest point for only a moment, and then you fall down again. When I played Qg8 and thought I was losing, this immediately ran in my ears. You are at the highest point only for a moment’

That familiar sinking feeling, thought of here in terms of a descent. Not a bad analogy in terms of a career but in a game your opponent influences the direction you move in just as much as you do in chess, especially if they blunder.

MJM